AI in Bio • Sponsored by Lantern Pharma

How AI Empowers Biomarker-Driven Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are the lifeline of modern medicine, bridging the gap between lab-borne scientific discoveries and the availability of life-saving treatments for patients. Unfortunately, the success rate of clinical trials, particularly in the field of oncology, is not as robust as one might hope. In fact, a 2019 study of 7,455 interventional phase trials in oncology conducted from 2000 to 2015 suggests an estimate that only 3.4% of cancer drugs that enter Phase I clinical trials ultimately receive FDA approval. Many of these failures can be attributed to obstacles such as poor trial design and inefficient patient selection, often resulting from a lack of biomarker-driven insights. As a result, drug development can be a laborious and expensive process, with the cost of bringing a new drug to market estimated to be around $2.6 billion. As we grapple with these challenges, there is an urgent call for more efficient and targeted methods of drug development, and the answer may lie in the utilization of novel actionable biomarkers and the power of artificial intelligence (AI) to plan and execute clinical trials. For instance, IQVIA's artificial intelligence-based platform, using their Real World Data assets, have enabled precise patient and healthcare professional (HCP) targeting, doubling identified eligible patients, finding 30% more with uncontrolled symptoms, predicting 81% likely to quit treatment early, pinpointing events linked to early discontinuation, and boosting treatment transition success by 500% compared to prior methods.

What is a clinical trial?

Clinical trials form an integral part of the drug development process. They are carefully designed studies involving human participants, undertaken to determine the safety and efficacy of a new drug or medical device. This process is usually divided into four stages. Phase I trials primarily assess safety and dosage in a small group of healthy volunteers or patients. Phase II trials involve a larger group of patients and aim to assess the drug's efficacy and side effects. Phase III trials test the drug in an even larger group of patients over a more extended period to confirm its effectiveness, monitor side effects, and compare it to commonly used treatments.

Designing clinical trials for central nervous system (CNS) drug evaluation, for example, for brain tumors, represents an additional challenge due to unique properties of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). The BBB's unique and stringent selectivity often necessitates the implementation of specialized Phase 0 trials in CNS oncology programs. Because of BBB, these trials require higher systemic drug concentrations to achieve detectable levels within the CNS, as compared to other therapeutic areas, increasing the complexity and risk of the process.

RELATED: AI Breaches the Barrier Towards Better CNS Drug Discovery

The arena of clinical studies encompasses various approaches, including double-blind studies and more transparent strategies like open-label trials. With high failure rates in drug development, biomarkers are emerging as pivotal components of clinical trial experiment design, refining patient selection for more accurate outcomes. The trend towards using master protocols indicates a push for efficiency, as this model allows simultaneous examination of various treatments. More specialized frameworks, like basket and umbrella trials, further incorporate factors such as genetic biomarkers, reflecting the industry's shift towards more nuanced methodologies.

The Evolution of Clinical Biomarkers

Advancements in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and our understanding of the human genome have revolutionized the field of biomarker discovery, particularly in oncology. Traditional biomarkers often utilized circulating markers in blood, plasma, and serum, or those detectable through imaging techniques. However, with the advent of genomics, we have been able to delve deeper, identifying individual genetic variations that play pivotal roles in disease pathology, specifically in cancers where genetic mutations often take center stage.

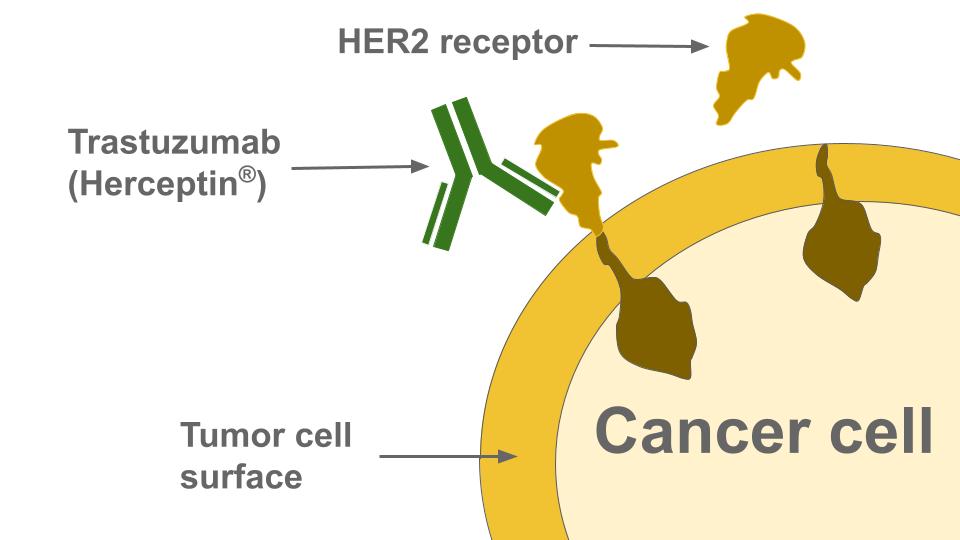

One of the defining moments in this biomarker-led therapeutic revolution was the approval of Herceptin (trastuzumab), a monoclonal antibody, by the FDA in 1998. Designed to target the HER2 protein, it was used to treat HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer, either as a first-line therapy in combination with other drugs, or as a standalone second-line treatment. This represented a significant stride forward in targeted cancer therapy, and opened the floodgates for similar advances. Today, we have a plethora of HER2-targeting drugs, including Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) such as neratinib, lapatinib, and tucatinib, which have broadened the therapeutic scope beyond breast cancer to other cancers that overexpress the HER2 protein or exhibit HER2 gene amplification.

HER2's sibling in the human epidermal growth factor receptor (ErbB) family, EGFR (also known as HER1), has been another game changer in the oncology biomarker landscape. EGFR mutations or overexpression are commonly found in many cancers, including glioblastoma, lung cancers, colorectal cancer, head and neck cancer, and breast cancer. The development of EGFR-inhibiting drugs such as TKIs (erlotinib, gefitinib, lapatinib) and monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab and panitumumab) have further emphasized the significant role of biomarkers in targeted cancer therapy.

Biomarker-driven clinical trials

The story of biomarker evolution in oncology doesn't stop here. Apart from HER2 and EGFR, numerous other biomarkers like KRAS, BRCA1/2, and PD1/PD-L1 have shaped the therapeutic strategies for several cancers, including breast cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and ovarian cancer. Additionally, an astounding number of 76 biomarkers have been identified as potential indicators of tumor invasiveness, including S100 proteins, annexins, galectins, CATD, TGM2, gelatinases, fibronectins, proteoglycans, TGFBI, FGG, APMAP, and more. The oncology biomarker discoveries underpin a remarkable shift towards personalized medicine, where treatment decisions are increasingly driven by the individual patient's unique genetic makeup.

In the intricate world of clinical trials, biomarkers serve as a guiding light, enabling more accurate prediction of therapeutic success and shaping the course of personalized medicine. Their contribution to medical progress has been highlighted by a comprehensive study that scrutinized over 10,000 clinical trials and focused on 745 drugs. The findings are powerful: introducing the factor of biomarker status significantly improved the prediction model for the trajectory of drugs throughout different clinical trial stages.

The 2021 study published in Cancer Medicine, employed two Markov models, which represent a statistical method that calculates the probability of transitioning from one state to another. When observing the effects of biomarker application across various types of cancers, the advantage was clear. The hazard ratios – the probability of a drug's approval – were significantly elevated when biomarkers were employed. For all indications combined, there was nearly a fivefold increase in the chances of drug approval. The most striking improvements were seen in specific cancers: a 12-fold increase for breast cancer, an 8-fold boost for melanoma, and a 7-fold growth for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Even for exploratory biomarkers that are not yet FDA approved, the model incorporating these biomarkers outperformed the model without biomarkers by 4-fold.

Nevertheless, biomarkers are not a foolproof guarantee of success. If they are not fully validated, they can potentially contribute to unsuccessful clinical trial outcomes.

Artificial Intelligence -- a game changer in clinical trials

In the modern era, Artificial Intelligence, or AI, has found utility across a diverse range of sectors, including healthcare. AI refers to the development of computer systems capable of performing tasks that typically require human intelligence. It encompasses a range of applications, from learning from experience and interpreting complex data to drawing conclusions and making decisions.

Now, the world of clinical research, particularly biomarker-led trials, is witnessing an AI revolution. The sheer complexity and volume of data in these trials call for a technological intervention. AI, with its capacity to process vast amounts of data, detect potential biomarkers, and even forecast patient responses, is transforming how clinical trials are designed and executed. Already now, AI-powered tools demonstrate tangible improvements in oncology clinical trials, such as a 50% increase in identifying potentially eligible patients and a 25% reduction in time for patient screening. Moreover, in automating trial matching and eligibility determinations, AI algorithms, applied to both structured and unstructured data, have achieved accuracies up to 87.6% with agreements between manual professionals and AI algorithms ranging from 81% to 94% in areas like breast cancer trials.

AI-based platforms are becoming transformative tools in the clinical trials landscape. Notable companies like Lantern Pharma, Owkin, and Biotx.ai, to name a few, are leveraging AI platforms for improving drug discovery and clinical trials, marking strides in the industry.

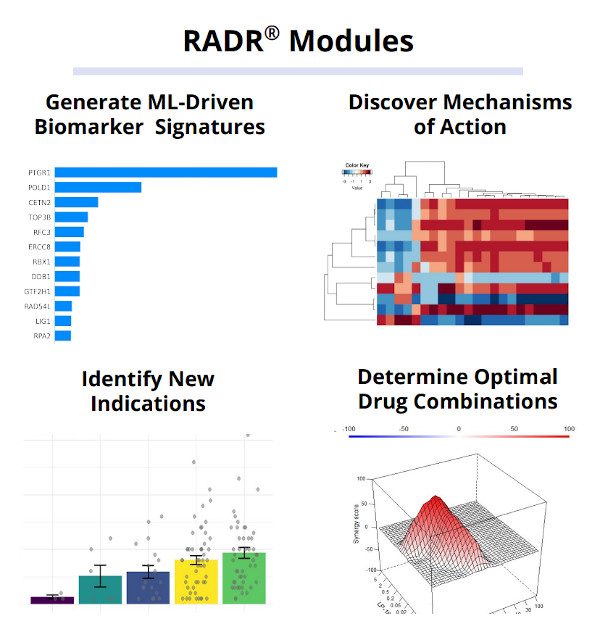

To illustrate this, Dallas-based clinical-stage precision oncology company Lantern Pharma, for instance, developed AI drug discovery platform RADR® which leverages transcriptomic, genomic, and drug sensitivity data from diverse sources, analyzing a vast volume of over 25 billion clinical data points, 154 drug-tumor interactions, and 130,000+ patient records across 17 databases. By integrating public resources, commercial studies, and Lantern's ex vivo 3D tumor models, the platform establishes correlations between genetic biomarkers and drug activity. Through this comprehensive approach, RADR® enables the transformation of multi-omics data into predictive models, facilitating the identification of candidate biomarkers and enhancing patient stratification for optimized clinical trial design.

RELATED: How AI Enables Precision Oncology

Utilizing their RADR® platform, Lantern Pharma tapped into AI to uncover the crucial role of the biomarker PTGR1 for their drug candidate LP-184. With this AI-led guidance, it became clear that LP-184 could be particularly effective against cancers with DNA Damage Repair (DDR) vulnerabilities. This insightful revelation, rooted in artificial intelligence, has paved the way for LP-184's upcoming clinical trials, aiming to target specific cancers such as pancreatic, prostate, ovarian, and breast that exhibit HR/NER pathway discrepancies.

In another example, Paris and New York-based precision oncology company Owkin developed AI-driven biomarker models to predict treatment response to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) and prognosis in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) patients from clinical and histological data.

Owkin collaborates with leading academic centers to curate deep, multimodal data that is AI-ready, and they are developing a technology platform, Abstra, designed to expedite AI biomedical research by helping researchers discover collaborators and datasets. Through the application of AI to this rich data, they subtype patients, pinpoint novel biomarkers, and enhance drug discovery while reducing clinical trial risks.

RELATED: Owkin Advances AI in Drug Discovery with Launching $50 Million MOSAIC Project

Berlin-based Biotx.ai utilizes a combination of expert judgment, mechanistic validation, and artificial intelligence to identify drug candidates poised for success in phase IIb. Led by Jack Scannell, the expert drug selection committee assesses treatments using their synthetic clinical trial platform, which predicts drug efficacy and side effects based on independent mechanistic models. These potential treatments are unearthed using unique wide data algorithms that uncover intricate relationships between genes, revealing links between drug targets and diseases. Instead of the common big data approach, Biotx.ai focuses on wide data, deciphering complex patterns from limited examples by employing knowledge graphs to simplify hypothesis spaces, using predictive power algorithms. Their prowess was evident when they identified a link between variants on the CDK6 gene and severe COVID-19 outcomes, which was subsequently verified by the University of Bristol through in-vitro testing.

Practical Case Study: an AI approach to biomarker-driven clinical trials

Having reviewed general tendencies in how AI-enabled precision biomarkers can help improve clinical trials, let’s focus on a practical case study.

Lantern Pharma employs a distinctive approach to drug development. Rather than developing drugs from the initial stages, they turn their attention to late-stage clinical drugs which demonstrated efficacy in certain patient demographics but were, for various reasons, set aside.

Their strategy involves leveraging advanced genomics, data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI). They use these technologies to 'rescue' these potential drug candidates and reroute them towards the precise patient groups identified through molecular profiling. This methodology creates opportunities for more efficient and focused patient treatment in clinical trials.

This approach is being utilized in Lantern Pharma's current collaborative programs. They're working with Actuate Therapeutics on the development of Elraglusib, now in Phase 2 of its clinical trial, and TTC Oncology for TTC-352, currently in Phase 1, among other numerous collaborations.

Lantern’s AI drug discovery platform has shown to be effective in predicting the responses of patients to certain drugs. One such example is its work with Elraglusib, a drug used to treat patients with metastatic melanoma resistant to checkpoint inhibitors. The RADR® AI platform was able to predict the drug's response with an accuracy rate of 88% across all solid tumors being tested for Elraglusib; using those models they were also able to predict sub-populations of melanoma patients that may benefit from Elraglusib.

This kind of precision in prediction can significantly enhance the prospects of stratified medicine, leading to more efficient, cost-effective drug development and deployment. The work of Lantern Pharma provides a concrete example of how AI can be effectively integrated into biomarker-led clinical trials. As medical research continues to evolve, AI-driven strategies such as these will likely play an increasingly important role in creating more personalized healthcare solutions.

Topic: AI in Bio